We are at a crisis point, indeed. However, lost in all of this hoopla is that this isn't a foreclosure crisis, but a housing affordability crisis. You need no proof aside from the fact that foreclosures began to spike in a time of extremely low unemployment and a generally strong economy. Prior, foreclosures have largely been a symptom of economic hardship, not the cause. Many cannot afford to handle a "market" housing payment even at today's somewhat reduced values. For those who can, paying off our housing debt continues to suck up valuable income that can be used to buy goods and services and stimulate the economy.

As I've said before, either incomes must rise dramatically (unlikely given the economic outlook) or housing prices must fall dramatically (10-15% with stable interest rates) before the system regains equilibrium. In this housing fiasco, where the order of magnitude stretches into the trillions, there is literally nothing we can (or should try to) do to stop this process from occurring.

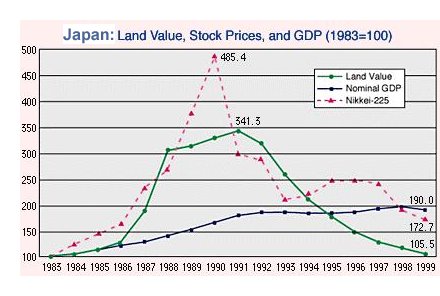

Unfortunately, some of us, especially those desperate to hold onto political offices, feel like we should try. Some folks across the Pacific in Japan thought the same thing back in the 1990s. Let's see how that turned out...

Thanks to Charles Hugh Smith, from whom I borrowed the chart above.

From Wikipedia on the Japanese RE bubble:

The easily obtainable credit that had helped create and engorge the real estate bubble continued to be a problem for several years to come, and as late as 1997, banks were still making loans that had a low guarantee of being repaid. Correcting the credit problem became even more difficult as the government began to subsidize failing banks and businesses, creating many "zombie businesses".

The time after the bubble's collapse (崩壊, hōkai?), which occurred gradually rather than catastrophically, is known as the "lost decade" (失われた10年, ushinawareta jūnen?) in Japan. The Nikkei 225 stock index eventually bottomed out at 7603.76 in April 2003 before resuming an upward climb.

Instead of letting things get back to normal, where people had to be able to pay for stuff out of their incomes, Japan struggled mightily to prop up failing banks and dwindling asset prices. Despite Japan's sincerest efforts, this only served to prolong the agony and balloon the national debt, leading to Japan's "lost decade." Today, due to the bloated cost of government bailout programs during the last 15 years, 70% of Japan's tax revenues are dedicated to servicing debt, up from about 30% prior.

The lesson: We have to take our medicine one way or another, and quick and painful seems much better than prolonged and agonizing.

We haven't seem to have gotten the message. Just when I thought we couldn't get any denser, Ben Bernanke comes out of the woodwork and says that lenders should simply reduce the amount people owe on underwater loans. Am I missing something here? Gee, instead of keeping the loans the way they are and the lender collecting 3/4 of the money... why don't we all just "fuhgeddaboudit" and reduce the principal wholesale, so the lender loses the 1/4 he was going to already along with the 3/4 he would have collected anyway? Who needs all those hundreds of billions anyway? Brilliant (sarcasm).

That's even better than the "negative amortization certificate" idea where banks would buy underwater loans, reduce the principal owed and get a warrant for the reduction amount, which they could collect with interest when the house is eventually sold, provided it sells for enough to cover both the mortgage and the warrant. Hmmm, so why wouldn't I just sell my house to get rid of your warrant and buy a similar house? That way, I wouldn't have to pay anyone when I sell...

Ridiculous... I hope we all don't lose a decade because of this...

Bernanke Says Homeowners

Need More Help on Loans

By MICHAEL R. CRITTENDEN

March 4, 2008 4:35 p.m.

ORLANDO, Fla. -- More needs to be done to help troubled homeowners, including a broader effort to write down the principal of some problem loans, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke said Tuesday.

![[Ben Bernanke]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/HC-GG945_Bernan_20070329150953.gif)

"In this environment, principal reductions that restore some equity for the homeowner may be a relatively more effective means of avoiding delinquency and foreclosure," Mr. Bernanke said in prepared remarks. (Read the full speech.)

Speaking at the Independent Community Bankers of America conference in Orlando, Fla., Mr. Bernanke said the current turmoil in the housing market "calls for a vigorous response."

"Efforts by both government and private-sector entities to reduce unnecessary foreclosures are helping, but more can, and should, be done," Mr. Bernanke said.

Though most loan modifications by lenders have focused on reducing the interest rate on a borrower's loan, Mr. Bernanke said a reduction in the principal might be more appropriate. Specifically, with many borrowers owing more on their home than the value of their mortgage, "a reduction in principal may increase the expected payoff by reducing the risk of default."

Mr. Bernanke also suggested a number of policy options that could help the current situation. Reforming the Federal Housing Administration, including giving the agency more latitude to set underwriting standards, could help reduce foreclosures.

Additionally, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac could have a bigger role in dealing with the current problems if both companies raise more capital, Mr. Bernanke said.

"New capital raising by the GSEs, together with congressional action to strengthen the supervision of these companies, would allow Fannie and Freddie to expand significantly the number of new mortgages that they securitize," Mr. Bernanke said.

Write to Michael R. Crittenden at michael.crittenden@dowjones.com

![[Hillary's Bad History]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/AG-AA869_1japan_20080330205420.gif)

That means real estate slumps tend to grind on for years, until sellers submit to reality and reduce their prices.

That means real estate slumps tend to grind on for years, until sellers submit to reality and reduce their prices.

![[Ben Bernanke]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/HC-GG945_Bernan_20070329150953.gif)